Introduction

At the forefront of the global data protection regimes is the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a trailblazer in establishing robust norms on data protection. Entering this dynamic landscape is India’s first proper data protection law, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP). This new law signifies India's commitment to aligning with global standards of data privacy while addressing its unique socio-economic context.

For corporations that are subject to both GDPR and DPDP, comprehending the similarities and distinctions between these two regimes is crucial to ensure seamless compliance. Equally, for Indian enterprises that are relatively new to comprehensive data protection frameworks, this article offers practical insights.

Scope and Applicability

The GDPR and DPDP Act share a broad territorial scope, impacting entities beyond their geographic borders. Both apply to organizations processing personal data within their regions or targeting their residents from outside.

They differ in their material scope but not by much. The GDPR casts a wider net over 'personal data' which encompasses any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. This definition is broad and includes online and offline data, digital and manual records, provided they form part of a filing system.

In contrast, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act narrows its focus to ‘digital personal data’. While it does cover data that is collected offline but digitized, its scope does not extend to all forms of offline personal data.

Definitions

Personal Data

In the GDPR framework, personal data is meticulously classified, with 'special categories of personal data' being a key subset. This includes sensitive information like racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, and religious beliefs. These categories necessitate varying compliance measures, especially regarding the lawful basis for processing.

The DPDP Act covers all personal data within the digital realm, without differentiating between sensitive or critical categories. This means the DPDP Act does not impose varied compliance standards for different data types, leading to a consistent standard across all personal data classes.

Consent

The definition of Consent is almost identical in the two laws both requiring Consent to be free, specific, informed and unambiguous with a clear affirmative action. The DPDP Act uniquely adds the word ‘unconditional’ in the definition making consent slightly more robust. However, the understanding is largely the same across the two laws.

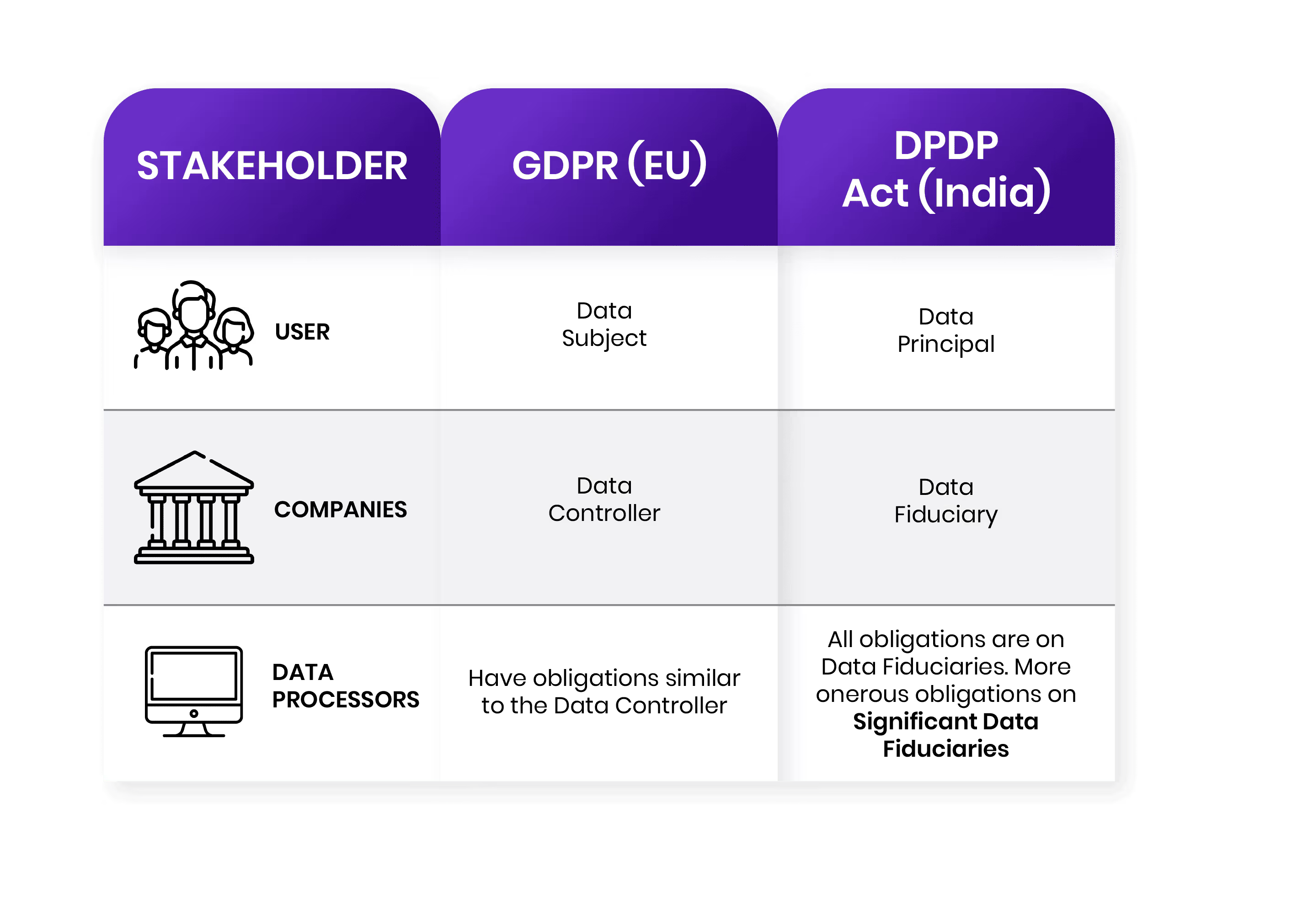

Stakeholders

The individual whose personal data is being processed is called 'Data subject' under the GDPR. The DPDP Act refers to them as 'Data Principals,' maintaining the individual-centric approach of GDPR.

Both laws grant rights to these individuals over their data such as right to correction, erasure, information, grievance redressal etc. Notably, the GDPR grants more rights that are not expressly offered by the DPDP including the ‘right to data portability’ and ‘right against automated decision making’.

Under the GDPR, the entity that determines the purposes and means of processing personal data is known as the 'Data Controller.' Similarly, the DPDP Act introduces the concept of a 'Data Fiduciary,' mirroring the role of a data controller in GDPR. The term 'fiduciary' implies a relationship of trust and responsibility towards the data principals. Both laws impose obligations of data protection and processing on Data Controllers/Fiduciaries.

The DPDP Act further distinguishes some fiduciaries as 'Significant Data Fiduciaries' based on criteria such as the volume and nature of data processed. This classification under the DPDP Act suggests a nuanced approach to regulation, imposing additional responsibilities on certain types of fiduciaries.

Entities that process data on behalf of the controller without determining the means and purpose are called Data Processors under both laws.

The GDPR places direct compliance obligations on data processors also subjecting them to penalties for non-compliance. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act does not impose obligations on data processors. Instead, the responsibility lies with the Data Fiduciaries (controllers) to ensure compliance by the processors they engage.

Grounds of Processing

Both the GDPR and the DPDP Act establish specific grounds under which personal data can be processed, forming the legal basis for operations involving personal data.

The GDPR offers a wider list of lawful bases for data processing. These include consent of the data subject, performance of a contract, compliance with legal obligations, protection of vital interests, performance of a task carried out in the public interest, and legitimate interests pursued by the data controller or a third party. This variety provides flexibility for organizations to choose the most appropriate basis for different processing activities.

The DPDP Act provides a much narrower list. The primary ground is Consent of the data principal which is essential for most activities. Only in certain exceptional scenarios known as ‘certain legitimate uses’ will other grounds be allowed other than consent. These include activities necessary for the performance of State functions, compliance with law, response to medical emergencies, and employment related purposes.

Consent Managers

The streamlined focus of the DPDP on Consent is reflective of the Indian regime’s objective of putting user choice and empowerment at the very forefront. Since Consent is the most significant and common ground for processing under the DPDP Act, it uniquely provides for the concept of “Consent Managers”.

Consent Managers are entities registered with the Data Protection Board, responsible for managing and overseeing the consents given by data principals. They serve as a centralized platform for individuals to grant, review, and withdraw their consent, simplifying consent management in the digital ecosystem. Consent Managers may play a central role in not just enabling individuals but also easing the compliance burden of businesses.

Compliance and Obligations

The GDPR and DPDP Act establish a range of obligations for businesses, focusing on notice requirements, handling of data breaches, and the role of data processors. Here’s how these obligations differ between the two regulations.

Notice for Personal Data

The GDPR demands comprehensive privacy notices to be given to data subjects in all scenarios of personal data collection. The notice must include details about the data controller, the purposes and legal basis of processing, and rights available to data subjects, etc.

The DPDP Act stipulates that notices must be provided to data principals ONLY when consent is the basis for processing. This means if the data is being collected/processed for a certain legitimate use where consent is not required, there is no obligation to give a notice. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act uniquely mandates providing notice in local languages, enhancing understanding and accessibility for data principals.

Breach Notice

Notifications for breach of personal data must be given under both the laws.

Under the GDPR, breaches that may pose a risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects must be reported to the relevant authorities. Affected data subjects must be notified only if the breach is likely to lead to a high risk to their rights.

The DPDP has a stricter notice requirement mandating data fiduciaries to report ALL personal data breach regardless of their risk assessment, to the Data Protection Board and to the affected individuals.

Cross-Border Data Transfer

The transfer of personal data outside the EU is subject to strict regulations under the GDPR. It allows data transfer to countries deemed to have adequate data protection measures or through mechanisms like Standard Contractual Clauses or Binding Corporate Rules.

In contrast, the DPDP Act allows the Central Government to restrict the transfer of personal data to certain notified countries or territories outside India. The Act's approach is expected to be less prescriptive than GDPR, focusing more on governmental discretion to determine safe data transfer jurisdictions.

Children’s Data

The GDPR imposes strict conditions on processing children's data, especially in the context of commercial services and profiling. The GDPR follows a more flexible approach and sets the age of consent at 16, which can be lowered to 13 by member states.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 defines individuals below 18 years as children, requiring verifiable parental consent for processing their data. It specifically prohibits processing that is likely to cause harm to children, including targeting advertising.

Data Protection Officers

DPOs play a crucial role in advising on, monitoring, and ensuring compliance.

Both regulations mandate appointing Data Protection Officers for entities handling significant data volumes. The DPDP's specific requirements for DPOs will be detailed in upcoming rules.

Penalties and Enforcement

Summary

.avif)